July 1, 2029 was a special day for the Gomez family: it was the day they bought their first home.

Both Miguel and his wife Veronica were lifelong Angelenos who had worked their way into the middle class — Miguel was an accountant at a firm downtown, and Veronica was a trauma nurse at UCLA Medical Center. But their long car commutes to and from the Valley left them without enough time to spend with their three-year-old, Stephanie. With a boy on the way in November, they knew it was time to buy a home that better fit their needs.

They found the right home in a townhouse in Westwood, walking distance to a preschool and to Veronica’s hospital, and three blocks from the new Metro station that would get Miguel downtown in 25 minutes. Miguel’s mom, Angelica, had moved into a granny flat in the neighborhood the year before, and spotted the “For Sale” sign on the property. The townhouse was relatively new and spacious, and fit the family’s budget.

The Gomez family’s happy story, and thousands like it, were possible because Los Angeles had used the Twenties wisely, to fix the city’s longstanding problems and invest in a vibrant, prosperous, sustainable, and equitable future for all Angelenos.

After the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, Los Angeles experienced a homebuilding boom, with hundreds of thousands of new apartments built in high-opportunity neighborhoods near jobs and transit. New laws and funding programs ensured that a large share of these homes were affordable to Angelenos with lower incomes. City and state officials finally got serious about ending homelessness, prioritizing new investments in permanent supportive housing and healthcare services. The region doubled down on expanding Metro, recognizing that freeway widening and car dependency were futile and unsustainable. And a new state law allowed homes and stores near transit to be built without on-site parking, which reduced car dependency and housing costs.

As all these new homes were completed, rents and housing costs dropped, and homeownership rose as more families could afford their first home. Neighborhoods that had once been defined by exclusion became more diverse in every way. With more people able to live near transit and commute without driving, traffic fell and air quality became better than ever. Tents lining the sidewalks disappeared for good. And the cruel trend of families being priced out of their neighborhoods, and out of California altogether, finally reversed itself; in fact, working-class and middle-class people began moving to L.A. for good jobs and affordable homes.

That evening, Miguel and his mom took Stephanie to the neighborhood park for the first time. Her future, and the future of children all over Los Angeles, was bright.

—

This dispatch from L.A.’s future doesn’t have to live only in our imagination. It’s within our power to build this future, and it starts with implementing a smart and fair plan for ending our city’s housing shortage and affordability crisis.

Under California’s Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA), L.A. must develop a plan by October to encourage 456,000 new homes to be built by 2029, of which 184,000 must be affordable to lower-income households. This plan, called a “housing element”, should distribute new housing opportunities across L.A.’s neighborhoods, especially in high-income areas with good access to jobs, transit, schools, and parks. Reforming zoning and land use policies to achieve strong housing growth in high-opportunity neighborhoods is a path to lower housing costs, a healthier climate, less displacement, and a stronger economy.

That’s why Abundant Housing LA has joined with nearly 20 civic organizations to urge L.A.’s Department of City Planning and the City Council to develop and implement an equitable distribution approach to the housing element. We’re excited that the Los Angeles Times’ editorial board endorsed this path to solving the housing crisis, and that the City Council, under Council President Nury Martinez’s leadership, instructed Planning to develop an equitable distribution of L.A.’s RHNA target “around the city based on high-quality jobs, transit, and historic housing production.”

Unfortunately, Planning doesn’t seem to have gotten the message. In January, they published an initial study for the housing element that proposed no significant changes to land use rules. Instead of reforming zoning to encourage strong housing growth citywide, Planning’s approach would perpetuate housing scarcity and maintain exclusionary barriers in high-income areas, which would reinforce an unfair status quo.

Planning’s approach is unfair because it does not affirmatively further fair housing. Under state law, cities can’t perpetuate historic patterns of racial segregation when planning for future housing. Instead, housing elements have to actively encourage more integrated, inclusive communities, and plan for affordable housing growth in high-opportunity neighborhoods.

To plan for an equitable future, we need to first study the past: let’s understand how patterns of racial segregation were created through discriminatory laws and land use rules, and how these rules continue to divide L.A. by race and class, even today.

—

Until the 1960s, racist laws and practices, like redlining and restrictive covenants, were used to exclude Black, Latino, and Asian Americans from many neighborhoods and cities across the United States and throughout Los Angeles County.

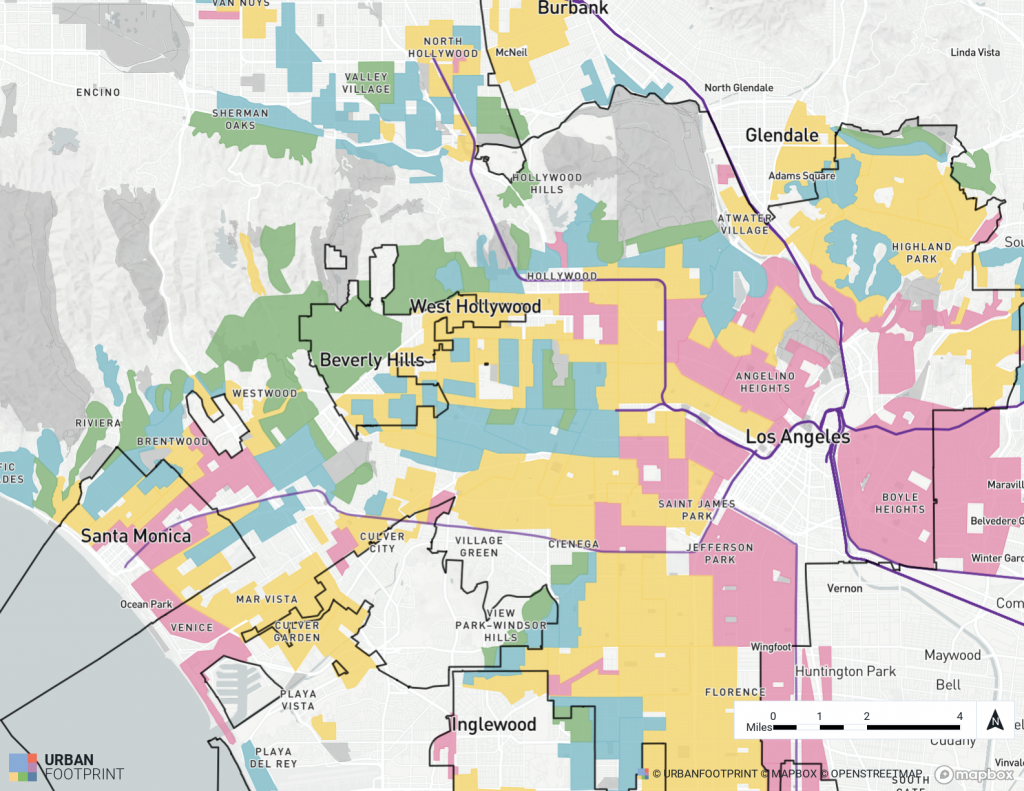

The map below shows how redlining divided L.A.’s neighborhoods into 4 categories. “Desirable” areas (green and blue) were usually majority-white, while “declining” (yellow) or “hazardous” (red) areas were often home to communities of color. This racist practice implemented discriminatory mortgage lending practices, and reinforced racial and class division in our city.

Home Owners’ Loan Corporation map of Los Angeles, 1930s

“Desirable” areas in green and blue, “declining” or “hazardous” areas in yellow and red

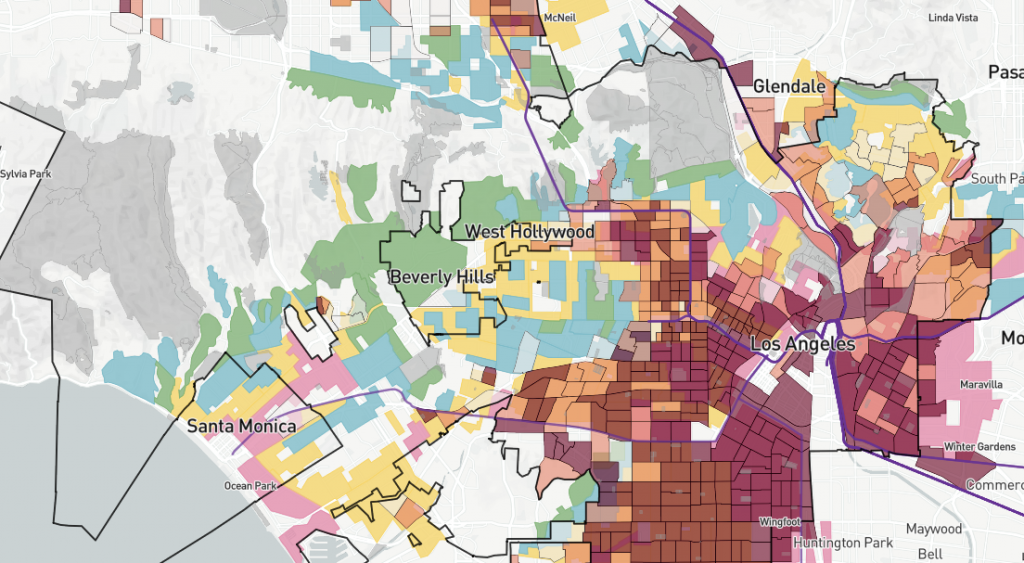

Though redlining and discrimination in lending have been illegal for decades, the barriers that redlining created live on through modern-day zoning in most American cities, including Los Angeles. This is because opponents of neighborhood change in prosperous, majority-white areas often weaponized zoning policy to make apartment construction illegal in these neighborhoods. This excellent article by Vox’s Jerusalem Demsas explains how these policies were deliberately used to restrict housing production and raise housing costs, which made it more difficult for Black families to move to high-opportunity areas with good schools, jobs, and public resources, and to build wealth through homeownership.

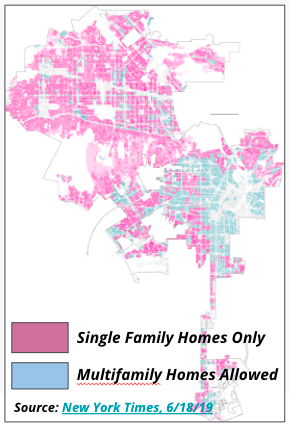

Today, 75% of Los Angeles’ residentially-zoned land is restricted to single-family housing only. Given that the median home price in L.A. is over $800,000, this means that housing opportunities are not affordable to most households in our city, particularly in high-opportunity Westside and Valley neighborhoods where exclusionary zoning predominates.

On the map below, we can see that areas where apartments are banned today (colored orange) tend to be ones that were defined as “desirable” during the age of redlining (colored green and blue), where Black, Latino, and Asian Angelenos were often not welcome.

Home Owners’ Loan Corporation map of Los Angeles, 1930s

“Desirable” areas in green and blue, “declining” or “hazardous” areas in yellow and red

Parcels where apartments are banned in orange

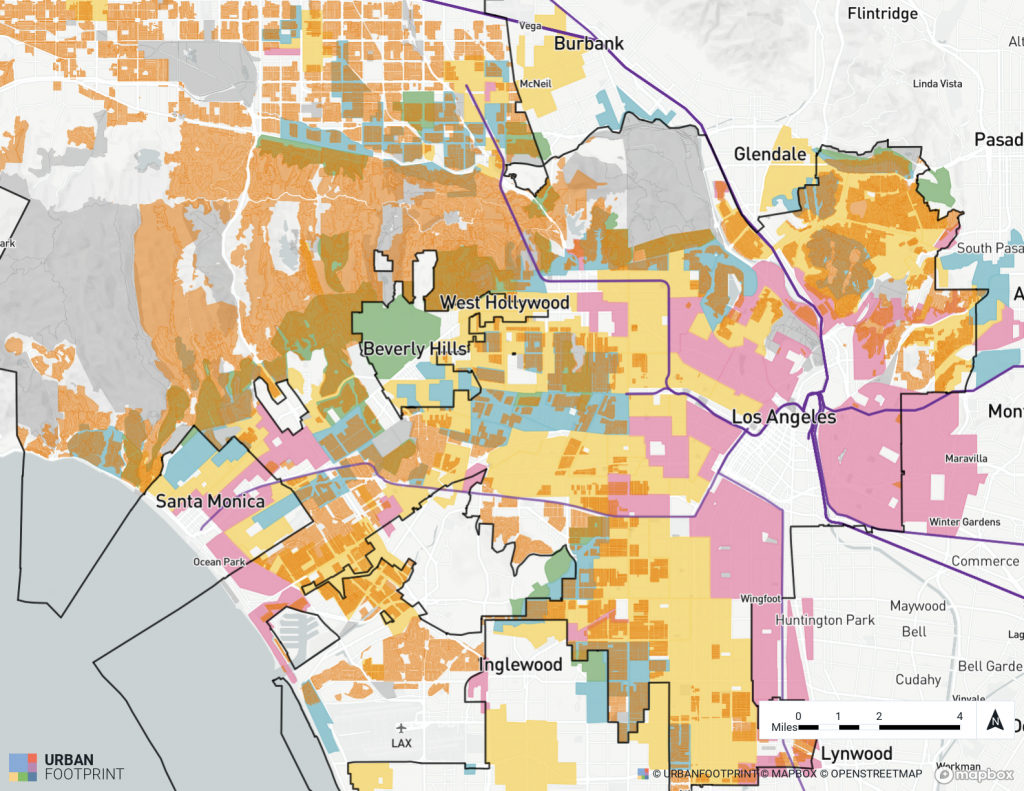

Exclusionary zoning therefore maintains discriminatory barriers that were outlawed decades ago, and prevents new housing opportunities for new neighbors in high-income areas. So it’s no surprise that areas that were defined as “desirable” during the age of redlining, where only white Americans could generally live, tend to have white majorities today. Areas that were defined as “declining” or “hazardous”, where zoning tends to accommodate multifamily housing, tend to be majority Black, Latino, and Asian today.

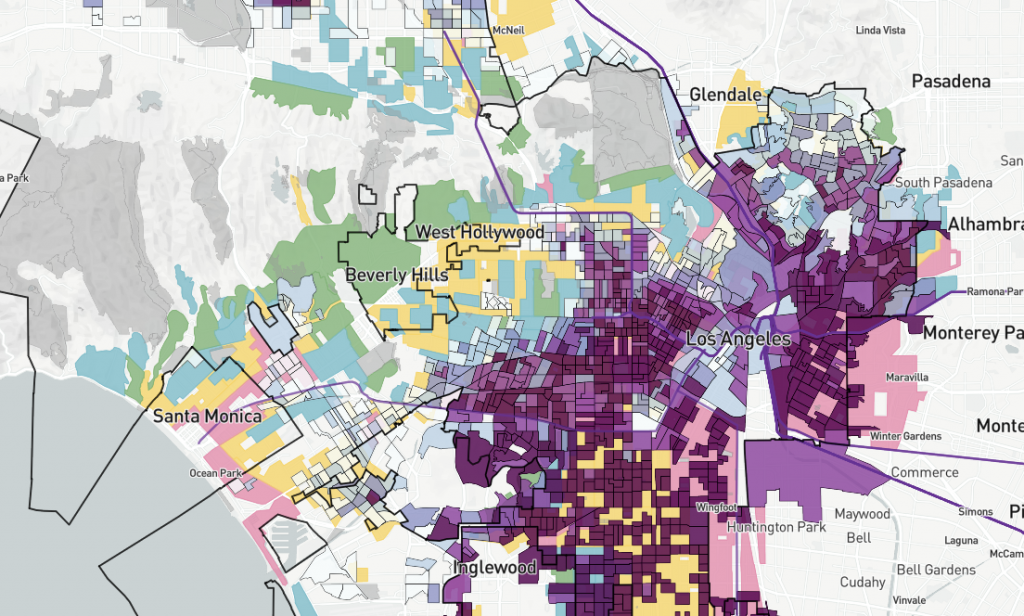

White Population of Los Angeles by Census Tract

“Desirable” areas in green and blue, “declining” or “hazardous” areas in yellow and red

Majority-white census tracts in shades of purple

Black + Latino + Asian Population of Los Angeles by Census Tract

“Desirable” areas in green and blue, “declining” or “hazardous” areas in yellow and red

Census tracts where Black, Latino, and Asian Americans are the majority in shades of purple

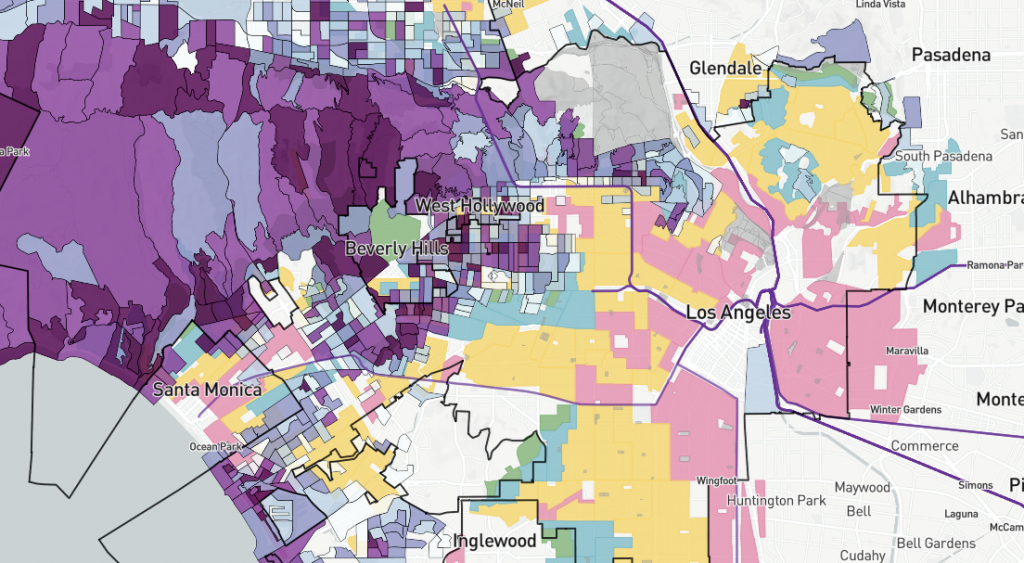

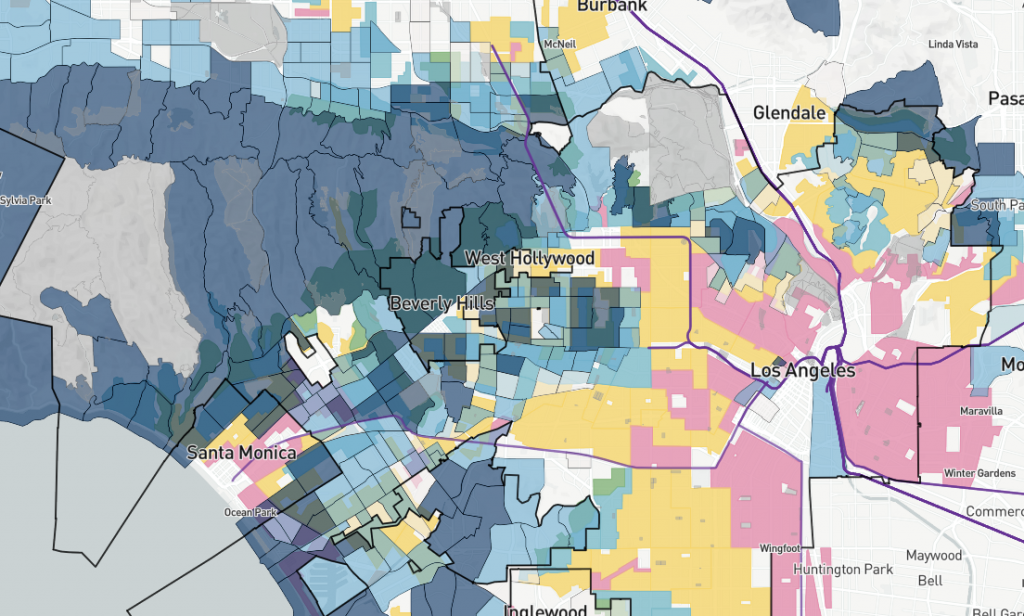

Neighborhoods that were defined as “desirable” when redlining was allowed also offer a higher quality of life today. The California Healthy Places Index is a social welfare index that measures overall quality of life in a neighborhood, based on factors like health, education, housing, economic opportunity, and transportation. Areas with higher Healthy Places scores frequently overlap with the green and blue “desirable” areas on the redlining map, while areas with lower Healthy Places scores tend to overlap with yellow “declining” and red “hazardous” areas.

Healthy Places Index Score by Census Tract

“Desirable” areas in green and blue, “declining” or “hazardous” areas in yellow and red

Census tracts with high HPI scores in shades of dark blue

Healthy Places Index Score by Census Tract

“Desirable” areas in green and blue, “declining” or “hazardous” areas in yellow and red

Census tracts with low HPI scores in shades of brown

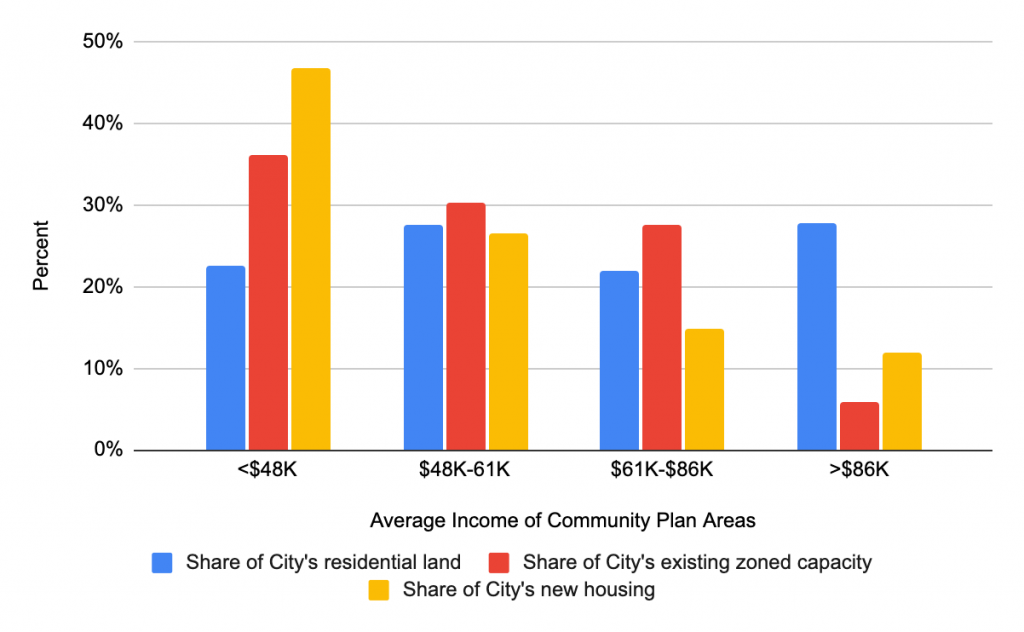

Zoning barriers also influence where new housing is (and is not) built in L.A. Since 2013, just 12% of L.A.’s new housing was built in high-income community plan areas (those with a median annual household income above $86,000), even though these areas make up 28% of L.A.’s residentially-zoned land. This is because only 6% of L.A.’s zoned capacity (i.e. space for building more homes) is located in these high-income areas, which is a function of exclusionary zoning.

By contrast, 47% of new housing was built in low-income CPAs (where the median annual household income is below $48,000), even though 23% of L.A.’s residentially-zoned land is located in these CPAs. Again, this is a function of zoning: 36% of the City’s zoned capacity is located in these low-income CPAs.

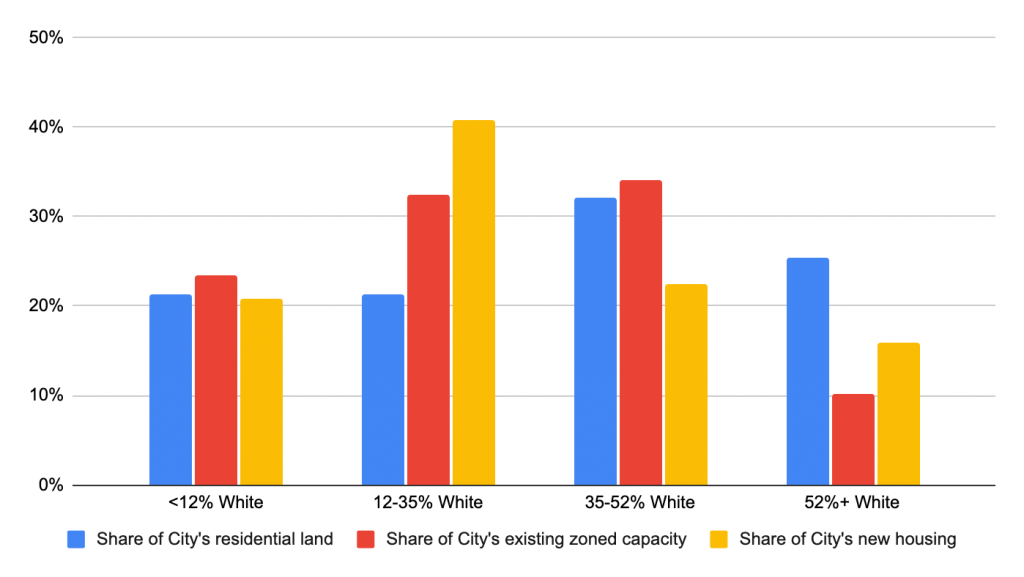

These same patterns emerge when we consider race. Areas with white majorities contain one-quarter of the City’s residentially-zoned land, but only 16% of L.A.’s new homes. But 60% of the City’s new housing was built in CPAs where the population is less than 35% white, despite having only 43% of the City’s residentially-zoned land.

(Credit is due to Dario Alvarez of Pacific Urbanism and Professor Paavo Monkkonen of UCLA Luskin for their analysis of CPA-level data in Los Angeles).

—

To summarize: racially discriminatory laws and practices from the past continue to haunt L.A. today, blocking many Black, Latino, and Asian Americans from building healthy and happy lives in neighborhoods that are rich with opportunity. Our housing laws pull us apart, when they should be bringing us together as one people.

This is why the status quo is unacceptable. This is why we need L.A.’s planners and elected officials to design a housing element that ensures that every neighborhood does its part to end housing scarcity and create opportunity for all Angelenos.

Of course, whether our leaders will actually do this depends on you. The NIMBYs and housing opponents are sure to fight back hard against housing reform, which is why you must make your voice heard on the need for more homes in more neighborhoods. There will be a critical opportunity to speak up early this spring, when Planning releases two important documents:

- The draft housing element, which will analyze where the City anticipates housing growth under existing land use rules and through rezoning

- The “equitable distribution” plan called for by Council President Martinez, which will propose citywide zoning reforms in order to meet L.A.’s RHNA target

Make sure that the City Council, Mayor Garcetti, and Governor Newsom know that you’re counting on them to encourage transformative, equitable housing growth citywide…because the hopeful and vibrant Los Angeles of 2029 is counting on you.