Anthony Dedousis, AHLA Policy & Research Director; Chris Elmendorf, Martin Luther King, Jr. Professor of Law at UC Davis; Esteban García, AHLA Communications Manager

Pro-housing advocates across California have been laser-focused on the Regional Housing Needs Assessment, a state-mandated process by which every city in California must develop a plan every eight years for meeting its housing needs (a “housing element”). While cities have historically shirked this responsibility, state law has been updated over the past few years to toughen up standards for the RHNA process. And thanks to the hard work of housing advocates, Southern California’s cities will be required to plan for over 1.3 million homes by 2030, with the majority in coastal urban centers.

Now that cities are beginning the process of updating their housing elements, city planners are looking to the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) for guidance on how to design housing elements that meet the state’s tougher standards. Last month, HCD posted a memo explaining how cities should identify locations for future housing development (a “site inventory”). While the report flew under the radar, its impact on housing growth throughout California could be significant, because it massively increases the amount of “zoned capacity” for new housing that local governments must provide.

How does the memo do this? As part of the process of creating a plan for achieving a city’s housing growth target (the “RHNA target”), a housing element’s site inventory must identify locations where the city expects new housing to be built, and estimates how many homes will be built in these locations. This means that how the city estimates a site’s potential for housing growth has a huge impact on how much housing is ultimately built.

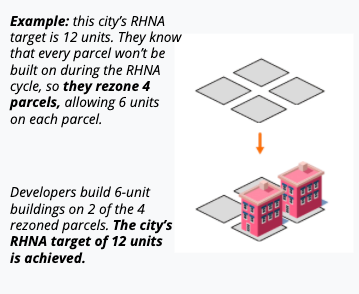

Of course, just because cities plan for more housing, doesn’t mean that the housing will be built. In past planning cycles, housing elements generally assumed that every parcel on the site inventory would be built to its theoretical maximum capacity, ignoring the likelihood that many of those sites will not actually be developed during the 8-year planning cycle. In planner-speak, they were not estimating the “probability of development” in the site inventory.

This was like a college undertaking to “plan” for a freshman class of 1,000 students by admitting just 1,000 applicants. No college would do that; instead, colleges estimate the probability that applicants will decline their offer of admission, and admit enough students in order to achieve a class size of 1,000 students.

Unsurprisingly, when local governments ignore the probability of development, they underbuild housing. The median local government in California is currently on track to develop only 25% of its RHNA target in the most recent housing element cycle (2014-21). Ignoring the probability of development offered cities a sneaky way to avoid housing growth while still being compliant with state housing law.

The tougher state laws that have been passed over the last few years, including AB 1397 from 2017, gave HCD the power to require cities to define sites’ housing capacity in terms of a realistic expectation of how many homes would be built on the site within 8 years.

And that’s what HCD’s memo does! They’ve made it clear that for a housing element to meet with their approval, cities will need to present a site inventory that estimates the “probability of development” at each location. They have to estimate a site’s “expected yield”, not its theoretical maximum capacity.

Again, for the median city, roughly one in four planned-for homes was ultimately built in the last housing element cycle. Using this as a rough rule of thumb for probability of development, you’d conclude that if a city’s housing target is 5,000 homes, it will have to provide zoned capacity for 20,000 homes. This marks a groundbreaking shift in how governments will have to rezone to accommodate more housing in more places.

This is great news…but it gets better. In 2018, AB 686, which requires housing elements to “affirmatively further fair housing”, was passed. This means “taking meaningful actions, in addition to combating discrimination, that overcome patterns of segregation and fosters inclusive communities free from barriers that restrict access to opportunity based on protected characteristics.” But what this meant in practice was left somewhat unclear.

Now, the memo explicitly states how HCD expects cities to affirmatively further fair housing. For the site inventory, locations identified to accommodate the housing needs of lower-income residents can’t just be concentrated in low-resource neighborhoods. Instead, HCD requires cities to distribute housing opportunities for people with lower incomes throughout the city, which is likely to require some upzoning of high-opportunity neighborhoods. Also, when preparing the site inventory, cities must specify whether the site can accommodate lower income housing, moderate-income housing, or above moderate-income housing, and use this information to demonstrate that the housing element will achieve the total demand for new housing across income levels (RHNA nerds call this “quantified objectives”). This is a big step in the right direction for having less segregated cities in California, and making it easier for people of color to live near good schools, safe streets, and vibrant job centers.

Of course, we know that NIMBYs never sleep, and that nothing fires them up more than a state agency telling them that they actually have to follow the law and allow more housing in their city. It’s on us to continue staying organized and pressuring city councils and planning departments throughout California to craft housing element plans that result in lots of dense housing actually being built, and people of all backgrounds having the opportunity to live in that housing.