Today, we’re kicking off a new blog post series, “Housing Across America”, which will dive into new housing laws and policy proposals across America’s cities. The housing crisis doesn’t just exist in California — the same pattern of housing scarcity, NIMBYism, rapidly rising housing costs, and insufficient funding for affordable housing can be found in most fast-growing cities across America. By looking beyond California to understand how other cities and states are addressing their housing crises, and which policies have been effective, we can better address the housing crisis here in Los Angeles and statewide.

Our series starts with a look at Massachusetts, which passed an economic development bill in January that requires cities in the greater Boston area to facilitate denser housing production around the T (Boston’s subway and train system). Our friends at Abundant Housing Massachusetts (no affiliation), who are dedicated local advocates for more housing and land use reform, were strong supporters of the bill.

Over the past decade, housing costs have increased rapidly in most major cities, as the supply of affordable housing has lagged behind strong demand. Boston is no different, with home prices increasing by 53% since 2009. Though the Boston area’s strong job growth and a growing preference for urban living have sparked greater demand for housing, rising housing costs are also a result of restrictive housing policies and local exclusionary zoning laws, especially in Boston’s suburbs. This has led to the same harmful trends that we’ve seen in California: longer commutes as lower-income households are pushed further from the city center, a sapping of economic vitality as employers struggle to attract workers who can afford high housing costs, and less economic opportunity for communities of color, who are harmed in particular when wealthier, majority-white cities and neighborhoods use exclusionary zoning to keep out new neighbors.

Fortunately, the state of Massachusetts has done what California has so far been unable to do: pass a major statewide zoning reform measure that encourages denser housing near transit. Massachusetts’ new law requires municipalities to legalize small apartment buildings in at least one district within a half-mile of a T station, allowing multifamily housing (apartments, condos, etc.) to be built in these areas without any special permits. The measure also requires cities to approve most zoning and land use changes by a majority vote, rather than a two-thirds vote, making it easier for cities to implement land use reforms locally. Finally, the bill puts $50 million towards affordable housing production in transit-rich areas and an additional $10 million for climate-resilient affordable housing. Cities that refuse to comply with the state law risk losing access to major state funding grants for housing and infrastructure.

As Rachel Heller, CEO of the advocacy group Citizens Housing and Planning Association, told the Boston Globe, “This would make a tremendous difference. The biggest barrier to building in Massachusetts is zoning and the lack of zoning for multifamily housing. People want walkable neighborhoods, and this will help us produce them.”

Despite strong opposition from some suburban legislators and political groups, Governor Charlie Baker signed this important bill into law on January 14. In a time of fierce political polarization, it’s worth noting that a Democratic state legislature and a moderate Republican governor were able to cooperate and pass a measure that will likely lead to the creation of thousands of new homes near transit in Boston’s suburbs. It’s also noteworthy that Massachusetts’ reform was incorporated into a larger economic development bill that had very strong legislative support. Housing policy is controversial, and packaging it with other important reforms helped to smooth the path to passage.

Transit-oriented housing development is not a new idea. Housing advocates and policymakers have long recognized the advantages of encouraging denser housing growth near public transportation. Living near public transportation means easier access to jobs and other economic benefits, while taking cars off the road and lowering carbon emissions. Although Boston has historically built denser housing around its transit lines, many of its suburbs have implemented exclusionary zoning even near transit. There are 38 cities that have MBTA stations, but no land that is appropriately zoned for denser housing.

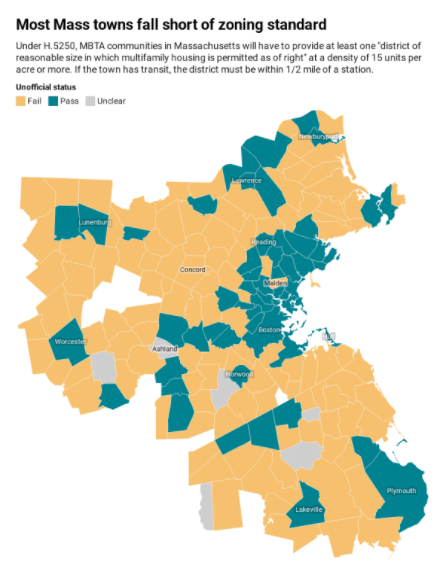

This helps to explain why a statewide bill overriding local zoning restrictions was ultimately necessary in Massachusetts. Salim Furth of the Mercatus Institute estimates that 115 cities in Massachusetts will need to rezone in order to be in compliance with the new state law. The bill nevertheless leaves cities flexibility in determining how and where to rezone near T stations in order to comply with the new state law. It thus allows local control while still holding cities accountable for planning for more housing.

This new law reflects a wider trend in Massachusetts of more policies that increase affordable housing production and reform exclusionary zoning laws. In October 2020, Cambridge passed a citywide affordable housing overlay (AHO), which legalized four-story apartment buildings in all residential neighborhoods and eliminated on-site parking requirements, so long as the units are affordable to lower-income households. This means that affordable apartment buildings can be built even on parcels that are currently restricted to single-family homes only.

Cambridge’s policy has inspired neighboring cities to take action as well. Newton, a prosperous Boston suburb, supported a new housing development policy in March 2020 and is now considering AHO-type legislation.

With Southern California cities generally resistant to reforming exclusionary zoning, even near transit and in job-rich neighborhoods, statewide reform is a necessary part of the formula for creating new housing in high-opportunity areas. Massachusetts’ example demonstrates that with the right approach, statewide housing reform is ultimately possible.