The holidays may be fast-approaching, but here at Abundant Housing LA, our scrutiny of bad housing elements continues. We’re delivering lots of coal to city councils that have spent the past year finding excuses for not encouraging housing growth and not ending exclusionary zoning, and we’re urging pro-housing city councilmembers to continue the fight for high-quality housing elements.

In recent weeks, we’ve also sounded the alarm about the recent adoption of deficient housing elements in Santa Monica, Long Beach, Whittier, and unincorporated Los Angeles County. We’re also keeping tabs on the Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD), to make sure that they don’t give in to NIMBY pressure and certify these substandard housing elements.

In housing element after housing element, we keep finding the same problem: most cities’ housing elements don’t identify enough land parcels to achieve their RHNA target. According to state law (Assembly Bill 1397, 2017), it isn’t enough to just create a list of parcels that theoretically have enough zoned capacity to accommodate the RHNA target. Cities have to also provide substantial evidence that these sites’ current use (e.g. a parking lot, a supermarket, an existing home) is likely to be discontinued over the coming 8 years, and that enough sites are likely to be redeveloped into housing to meet the city’s RHNA goal.

Cities whose housing elements don’t provide enough sites for housing redevelopment are very unlikely to achieve their RHNA targets, just as couples that invite 200 people to a wedding and expect 200 people to attend are likely to be disappointed. Recently, AHLA estimated that cities across Los Angeles County will only build 20-32% of their RHNA targets by 2029 if they fail to adopt high-quality housing elements.

Since we’re a pretty data-driven bunch at AHLA, we’ve partnered with MapCraft Labs, an economic and policy analysis firm with housing policy expertise, to forecast the true amount of housing growth that is likely to occur under 10 key cities’ proposed housing elements. MapCraft’s best-in-class analysis uses parcel-level zoning, building, and land value data, together with neighborhood-level rent estimates, to investigate cities’ claims about their site inventories (the list of parcels where the city claims residential redevelopment will happen), and sniff out assumptions that don’t align with reality.

For each parcel on a city’s site inventory, we found out:

- Whether projects of a similar size have been built on similarly-zoned parcels (or anywhere in the city) recently

- Whether projects of a similar size are currently being built on similarly-zoned parcels (or anywhere in the city)

- Whether the city’s land use regulations make redevelopment unrealistic

- If redevelopment of a site is realistic, what density can be expected given local housing demand (similar to a real estate pro forma analysis)

The first 5 reports, for Long Beach, Culver City, Whittier, Santa Monica, and unincorporated Los Angeles County, are live here. We’ll be uploading the last 5 reports (for West Hollywood, Torrance, Glendale, Pasadena, and Burbank) in the next week.

Like what you are reading? Sign up to receive more content like this.

Here are our three main findings:

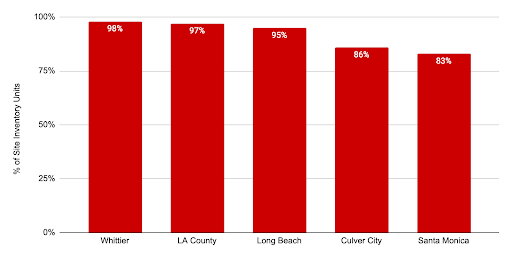

First: for each city we analyzed, over 80% of the housing units claimed in the site inventory are on parcels where redevelopment is unlikely (either to the density that the city is claiming, or altogether unlikely). For Long Beach, unincorporated Los Angeles County, and Whittier, over 95% of the claimed housing units fall into this category!

Percentage of housing units in city’s site inventory where the city’s redevelopment claim is unrealistic.

Again, these are sites where cities are claiming that redevelopment is likely to happen, even though they rarely provide strong evidence in their housing elements to support this claim. Cities need to account for the likelihood that most sites won’t be redeveloped in the near future. This happens for many reasons: the owner may not be interested in redevelopment, the existing businesses on a site may have long-term leases, etc.

Cities can encourage enough housing growth to meet the RHNA target by providing theoretical zoned capacity equivalent to a multiple of the RHNA target (this usually requires significant rezoning of low-density parcels). Unfortunately, the above five cities have not chosen this approach.

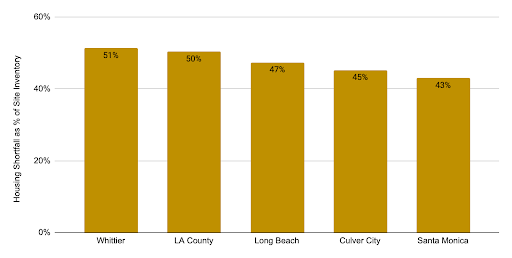

Second: because of these unrealistic claims, 40-50% of the housing units that cities are claiming in their site inventories are infeasible to build.

Since these 5 cities’ housing elements haven’t identified enough parcels where redevelopment is likely to happen, or rezoned enough parcels to encourage more construction, actual homebuilding in these cities will fall well short of their RHNA goals. Unfortunately, these housing elements maintain the fiction that nearly all site inventory parcels will be redeveloped by 2029, and our research shows that these cities are effectively relying on “phantom homes” to try to comply with housing element law on paper.

This imposes a real hardship on residents of our region. In these 5 cities alone, we estimate a collective shortfall of 55,000 homes, relative to their RHNA targets. This makes continued housing scarcity and high costs a virtual certainty.

Percentage of housing units claimed in cities’ site inventory that are infeasible to build.

Like what you are reading? Sign up to receive more content like this.

Finally, the good news: cities have many policy levers available to strengthen their housing elements and achieve their RHNA targets.

Our research shows that cities aren’t out of options; in fact, all 5 cities have substantial housing capacity “left on the table”. To increase homebuilding, cities should update their housing elements to rezone more sites where redevelopment is economically feasible, particularly for low-density parcels in high-demand neighborhoods where apartments are generally banned. In Culver City, that would mean legalizing apartments in more of the Washington-Culver, Carlson Park, Downtown Culver City, and Lucerne-Higuera neighborhoods. In Santa Monica, that would mean additional rezoning in Downtown, Mid-City, and Northeast Santa Monica.

Cities can also more aggressively rezone parcels that are already in their site inventory. Both approaches will add more market-feasible housing capacity to the site inventory, and result in more homes actually being built.

Cities must also adopt complementary policies that make redevelopment more feasible anywhere in the city, not just on rezoned parcels. One example is eliminating or reducing on-site parking requirements; our research finds that this would greatly improve the economic feasibility of denser housing development on many parcels. Cities also need faster, more predictable permitting processes where staff, not city councils or planning commissions, approve building projects (this also has the additional benefit of reducing influence-peddling and outright corruption).

As Ebenezer Scrooge in A Christmas Carol shows us, it’s never too late to change one’s ways. Cities still have until mid-February to improve their housing elements to encourage strong housing growth. And as for cities that have adopted deficient housing elements, our research will strengthen our case that HCD must reject these housing elements and ensure that these cities follow the law.

Like what you just read? Sign up to stay updated on housing!