This post is the second in a series: Lessons from a Pandemic. Read the first post here.

Housing after the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic

It’s too soon to answer these questions. But one factor worth considering is what happened after past pandemics. Just over a century ago, Los Angeles was hit by the global influenza pandemic, experiencing two waves of deaths and closures in late 1918 and early 1919.

How did these periods of infection and quarantine impact the city’s housing? We can consider it on two dimensions: health and building regulations and construction trends.

Health and housing

City planning and design has long been shaped by epidemics. Los Angeles established a Housing Commission in 1906 to investigate living conditions in so-called “slum courts”- predecessors of the bungalow courts built in great numbers in the 1920s. The commission and city council passed reforms to promote health, regulating plumbing and waterproofing and requiring at least 30% of the site be open space. At the state level, new building codes passed in 1917 for single dwellings, tenement houses (apartments), and hotels required more windows, larger interior light shafts and higher ratio of showers and bathrooms per home or hotel room.

After the Influenza pandemic, more health measures were taken, but they didn’t try to reduce residential densities. Los Angeles city adopted its first comprehensive zoning code in 1921. While the code established some of the first single family zones in the nation and barred business and industry from residential areas, it did not regulate the size and placement of houses and apartments or limit the number of homes in multi-family buildings. The same year, the city passed a “condemnation of unsanitary plumbing” ordinance regulating plumbing materials and water flow and allowing health officials to require the replacement of fixtures that didn’t connect to functioning sewers or cesspools.

It is worth noting that health measures were often justified and enforced in discriminatory ways. Many early 20th century health codes and campaigns implemented in Los Angeles focused on the “threat” that Mexican, Filipino and Chinese immigrants and predominantly immigrant neighborhoods supposedly posed to the public at large.

Housing Boom

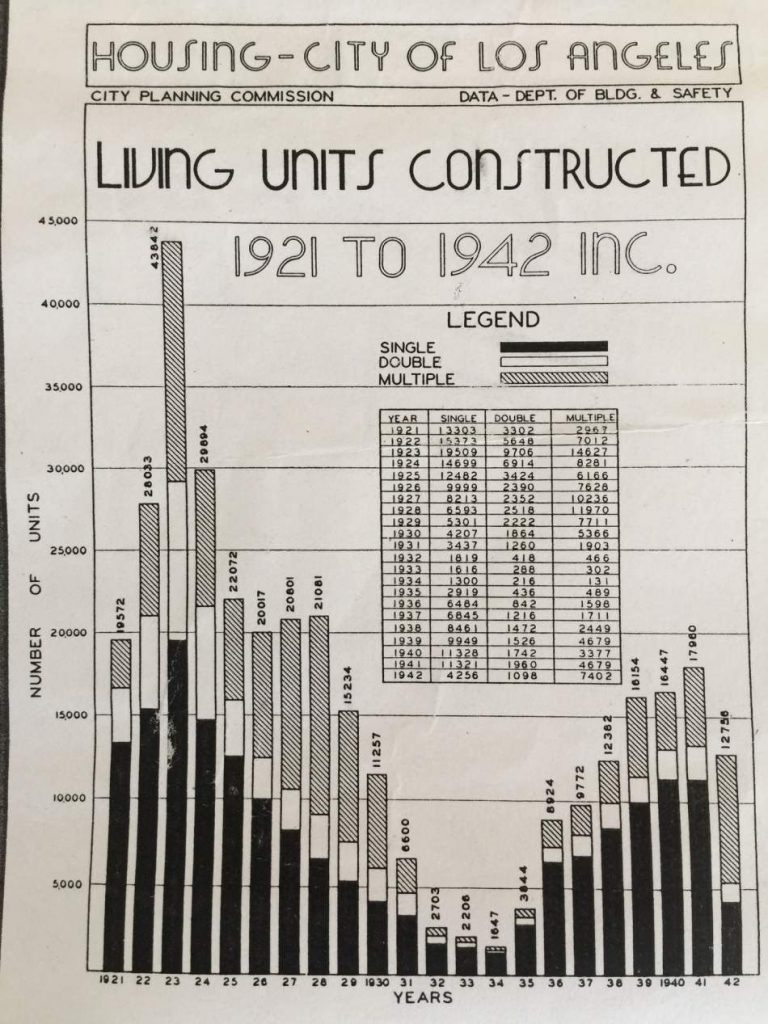

What about home building? In the decade after the influenza pandemic, there was explosive growth in housing production in the Los Angeles region. Like today, L.A. at the end of the first world war was experiencing a housing shortage and high rents. During the 1920s, in response to that pent-up demand and to rapid population growth, the City of L.A. permitted somewhere between 210,722 and 232,010 new homes.

To put these housing growth numbers into perspective, Los Angeles today has approximately four times the population that it did in the midpoint of the 1920. If we were building homes at the same rate as the 20s between 850,000 and 900,000 new homes would have been permitted in the past decade. In reality, approximately 115,000 new homes were permitted between 2010 to 2019– less than 1/7th the per capita rate of the post-influenza 1920s.