It’s housing element season here at Abundant Housing LA, as cities across Southern California publish their “housing elements”, which are strategic plans for achieving a housing growth goal over the coming 8 years. By October 15, as part of the state’s Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA) process, cities must adopt housing elements that identify quality sites for future housing, and institute zoning reforms that accommodate further housing growth and promote fair housing.

Well-designed housing elements can make our communities more affordable, equitable, and green by encouraging more housing near jobs, transit, and high-opportunity neighborhoods. That’s why AHLA has been putting cities’ housing elements under the microscope. We’ve written letters identifying shortcomings of draft housing elements, and shared our findings with the state Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD), which is empowered to approve or deny cities’ housing elements.

Unfortunately, most housing elements are missing the mark. NIMBY city governments typically claim that their cities have enough underutilized sites to achieve the RHNA housing growth target without rezoning, which is almost always untrue. Instead of legalizing more homes in areas where apartments are banned, these cities claim that housing will be built on unrealistic sites, like the South Pasadena City Hall, the Saban Theater in Beverly Hills, and even a San Diego cemetery. These cities have prioritized assuaging NIMBYs over solving the housing crisis.

Earlier this year, it looked like the City of Los Angeles was headed down a similar path. An early outline of the housing element made the dubious claim that the City could achieve its 456,000-home RHNA target with little change to housing policy. AHLA partnered with 13 other community organizations to push back against this “Status Quo” plan.

Fortunately, LA’s draft housing element, which was released earlier this summer, has a lot to like. Most notably, the City partnered with the Terner Center at UC Berkeley to create a statistical model to estimate LA’s current realistic capacity for new housing under current zoning. The model analyzed every parcel in the city, looking back at which parcels were redeveloped over the past five years in order to predict the likelihood of a parcel being redeveloped in the future, as well as how many homes would be built on a parcel if it’s redeveloped.

According to the model, LA will only build 10% of its RHNA target, or 45,000 homes, in a “business as usual” scenario without policy reform. This acknowledges that significant rezoning is needed for LA to achieve the RHNA target. No other city has taken this sophisticated approach to forecasting future housing production, and it’s encouraging that LA is leading the way, rather than playing games in order to avoid rezoning.

Another major win: the housing element echoed AHLA’s call for a “fair share” approach to RHNA rezoning. Under this equitable distribution strategy, new zoned capacity would be distributed to all neighborhoods, based on how each neighborhood scores on factors like access to transit, access to jobs, and housing costs. High-opportunity neighborhoods would accommodate the most new housing, including areas that have historically used exclusionary zoning to block housing and maintain racial segregation.

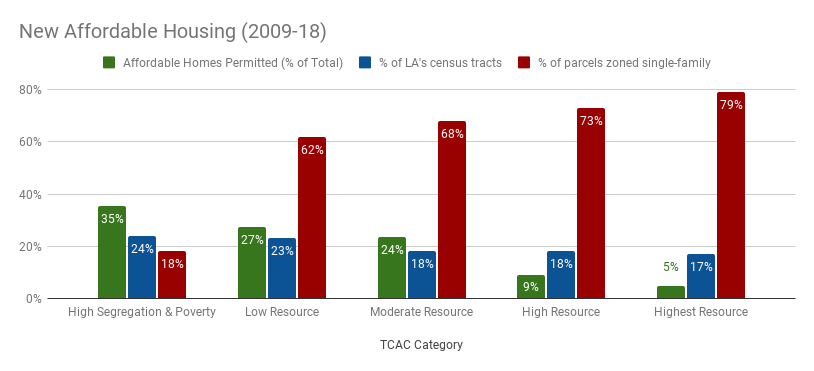

This is critical because restrictive zoning has discouraged housing production in LA’s best-resourced neighborhoods, raising housing costs, worsening segregation, and pushing lower-income households and communities of color out of LA. According to the housing element, just 14% of new affordable homes were permitted in high- and highest-resource areas since 2009, even though these areas make up 35% of LA’s total census tracts (in LA, a census tract is equivalent to a small neighborhood). This is because apartments are banned on 76% of the residential parcels in these well-resourced areas.

The housing element recognizes that a “fair share” approach to housing growth would encourage more affordable housing in high-resource neighborhoods and reverse patterns of segregation, an obligation under California’s Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) law. Recent policy reports commissioned by Councilmember Gil Cedillo and Council President Nury Martinez, as well as a comment letter on the housing element signed by Council President Martinez and six other councilmembers, endorse the “fair share” approach.

So then why only two cheers for LA’s housing element? Although the Terner Center capacity analysis and the fair share strategy represent significant progress, the housing element still contains some major shortcomings.

First, it doesn’t propose enough rezoning to achieve the RHNA target. While the Terner Center model forecasts individual parcel redevelopment well, the housing element makes aggressive assumptions about housing growth from other sources that don’t require policy changes. This includes housing projects that have been proposed but not yet built, ADU production, and affordable housing development on public land. It also counts anticipated redevelopment of parcels with rent-stabilized housing towards the RHNA target. The housing element therefore forecasts that about 33,000 homes will be permitted each year through 2029 without any rezoning, almost double the average number of homes permitted between 2017 and 2020 (17,800 homes). That doesn’t pass the smell test.

As a result, the housing element claims that LA only has to rezone for 220,000 more homes to achieve the 456,000-home RHNA target. We estimate that the true number is about 300,000 homes; fortunately, Council President Martinez and six of her colleagues have endorsed this higher RHNA rezoning target.

Second, it’s unclear how the City defines its rezoning target. Does the City plan to rezone for enough new capacity where 220,000 more homes could be built in theory, or will it rezone for enough new capacity to result in 220,000 more homes actually being built? This isn’t just semantics: as the Terner Center model shows, most parcels don’t get redeveloped in the near term, even if they have capacity for additional units. If the City only rezones to create 220,000 more units of capacity, just a fraction of that number will actually be built by 2029. If the City’s goal is to generate 220,000 more homes by 2029, then it must rezone much more.

This is similar to college admissions: when UCLA wants 2,000 students in its incoming class, they admit 3,000 students, recognizing that not all admitted students will decide to attend. Similarly, to achieve a housing growth goal, cities must increase zoned capacity well above the target number of new homes.

Finally, the housing element doesn’t include a concrete plan for land use reform and implementation. While it proposes some good high-level policy ideas, like expanding the City’s Transit-Oriented Communities density bonus program, it doesn’t provide specifics about where rezoning will happen, which constraints on homebuilding will be reformed or lifted, and how the housing element will promote lower-income housing opportunities in high-resource areas. The state law requires housing elements to include programs with concrete action steps to facilitate housing production, but LA’s housing element only offers loose goals and words like “plan”, “explore”, “consider”, and “examine”.

But there’s good news: LA has until October 15 to finalize its housing element and submit it to HCD for approval. AHLA has published a letter explaining the positives and shortcomings of the draft housing element, and recommended a concrete set of policy reforms, like:

- Rezoning for enough new capacity to result in 300,000 more homes being built by 2029

- Distributing new housing capacity across all neighborhoods, using a comprehensive fair share approach to rezoning

- Increasing affordable housing opportunities in high-opportunity neighborhoods by legalizing apartments where they’re banned, creating new funding sources to support affordable housing growth, and strengthening tenant protection policies

- Implementing policies that apply citywide, rather than relying on the City’s slow, broken Community Plan update process

- Expanding and merging TOC and the city Density Bonus program

- Removing unnecessary constraints on housing production: eliminate on-site parking requirements, legalize larger and taller buildings, and approve more projects by-right

LA’s housing element is promising, but we have one chance to get it right. Join us in telling LA’s leaders that you want a housing element that makes LA more affordable, equitable, and prosperous.